Vendor Collaboration in Drug Discovery

Building synergy and removing friction within the R & D vendor ecosystem

On our journey to discover and develop new treatments for patients in need, drug developers rely upon a large commercial marketplace for the goods, tools and services required to bring their own products to market. The intent behind this article is to share perspectives and tactics to operate with more synergy and less friction to reduce time and resources for new drugs reaching the hands of patients.

Note - I am NOT discussing CDMO and CRO collaborations here. This subject is left for an entirely different post, which honestly I won’t bother with until there are some tactics which have meaningful impact….I have not seen them yet.

Executive summary: align on realistic expectations and fulfill your commitments to improve your working relationship.

Fulfillment time for common supplies

For manufacturers and distributors of consumables, common reagents, and standard “off-the-shelf” equipment the customer request is “show me how much it will cost and how long it will take to help me decide where and what to buy. When I order it, make sure I get it on time.”

Upstream supply chain variations increase linearly with the number of suppliers each distributor has in their catalog. The complexity of gathering information about fulfillment from each supplier has out-weighed the cost to fix this challenge within the supplier organizations. Additionally, there are no good mechanisms for communicating this to the end consumers who need the goods. Neither drug developers nor vendors have implemented processes to provide transparency to the end consumer. What can be done?

On-site stocking programs

Vendor programs exist today to create “satellite distribution” locations within your company. These often require that your company meet a threshold of order volume or value. Frequent and accurate information provided directly to the end consumers about the managed supply and reduced inventory carrying costs are some of the ways this reduces fulfillment related friction.

If you have too many vendors (because your company is too big - don’t use more than two vendor operated stocking programs) or do not meet the thresholds for vendor managed programs (you are too small), it is valuable to create a role (even if part time) to create your own common inventory supply locations and manage the inventory through a central point of contact. In collaboration with procurement, this role will reduce friction by acting as a conduit between vendors and end consumers. This role can also use the tools you likely already have (LIMS, ELN, ERP) for active inventory management.

Use your procurement system data

The procurement system you loathe as an end user (joking…no not really) does track useful information. Rarely used (unfortunately), the information tracked by these corporate systems can create valuable transparency for your organization - order date, approval date, PO issuance date, vendor estimated delivery date, receiving date for example. If we are being real, most companies have a data scientist (or two) who are wasting time attempting to curate hopeless legacy scientific data for some of your projects. A MUCH better use of a small amount of their time is to grant them access to your procurement system and put together a simple search page which will show actual fulfillment timelines by product and vendor.

Technology Products & Projects

Unlike consumables, instrumentation and software products persist in the hands of the drug developers for years after purchase. The friction caused due to mis-aligned expectations about the product are largely preventable; moreover, these can usually be addressed during the diligence and implementation stages of the engagement.

While I am sure some will disagree (I welcome comments), my experience as consumer and vendor has given me these perspectives which you may find mutually helpful to keep in mind:

The objective for a vendor is to sell goods and services for maximum profit.

How can the buyer help the vendor? Don’t coax vendors into making bad decisions by making intractable demands which are not profitable for them.

The objective for drug developers is to produce some data or material with minimum resources.

How can the vendor help the buyer? Be honest. I’ve seen time and again where honesty earns trust and trust earns enough confidence in the vendor even to overcome gaps in product or support capabilities.

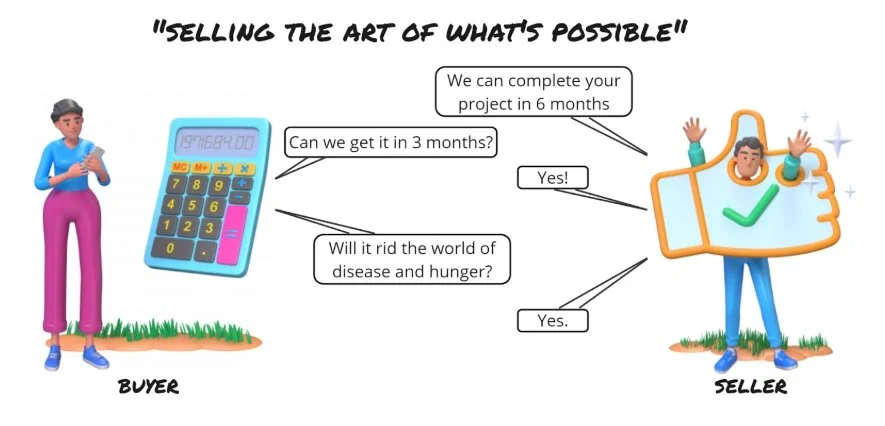

Be wary of future selling. It is not malicious, in fact, it is often the norm.

Product Selection

Instruments, software and other tech products are complex. Buying parties should use websites, whitepapers, and even journal searches to learn as much as possible about all of their product options before engaging with the vendor.

Pull together a team of stakeholders (anyone who will use or support the product and process) and prepare a written list of topics/questions about the product. This list consists of the information you didn’t find in your preliminary research.

I recommend email for first correspondence. However you prefer to engage, make sure to cover these bullets in your first engagement (assuming you have done the prelim research above):

What you like about their product and how you intend to use it

Your budgetary status because vendors also have to prioritize their resources

The list of questions your team pulled together above - ask that they be answered in a reasonable timeframe and followed up roughly 1 week later with a live session which includes the respondents to make any needed clarifications.

Live Vendor Demo

Get a live demo when possible. Be suspicious if you can’t get one, this likely means you are more of a development partner than a customer. This can be great, just be aware.

The customer should ask for specific things to be shown and the vendor should also have the freedom to demo the features which their existing customers love the most. For instrumentation, a live demo of the operating software is easy and impactful.

Implementation services and timeline

The vendor should provide their version of a successful project timeline, resources that the buyer should expect to commit, and the most critical project risks.

If the vendor “happy path” timeline is 2x the customer’s needed timeline, break it off immediately. If you are within 2x range, negotiate on what the customer can do internally or what additional service costs can be included to accelerate the project. The customer SHOULD NOT ask the vendor to agree to a timeline they can’t deliver upon without collaborating to provide the additional resource to fill the gaps…if you force that, the vendor will agree and you are both going to fail to meet your respective goals.

De-risking product through test drives

If the tech product you are evaluating is of any significance (say > $10K) then you likely want to do some additional diligence through hands-on time. With the exception of super easy-to-use SaaS software (almost non-existent in drug development) DON’T DO FREE TRIALS. It is bad for the vendor and the buyer.

For hardware, the customer should pay for one day of training and field service setup to ensure that this instrument is functioning properly for your testing over some feasible period of time. This will cost little and allow a proper assessment of the product. For software, purchase a period of time for access to the product, configuration of the product to fit your test user requirements, and standard support levels that you would receive as a permanent customer. Expect the cost to be 2-5K for a well supported hardware demo and add one zero for software (yes, in today’s fragmented IT ecosystem, 20-50K is nothing). Often you can collaborate on applying this as credit if a purchase is made.

Project Execution

In my experience, if you have aligned on the scope, contract, etc. before the project starts then the project will execute on schedule and on budget. Vendors generally have a good project management infrastructure when their product requires it. These project managers will work methodically toward delivery of your aligned scope.

A good collaboration between the vendor project manager and the buyer project manager will accelerate your teams. If you use the wrong project manager; however, you will actually add friction. Don’t put an IT project manager on a hardware project or vice versa. Even worse, don’t put a drug development project manager on any type of technology project. If you don't have the right fit, just let the vendor PM handle it.

Validation 😵

Sadly, I have no tactics to improve the process of validation. The rules and the methods for validation have not changed meaningfully in 2 decades (despite changing science). I look forward to AI-based tools to help with this effort in the near future.

I DO have a recommendation to critically evaluate where you truly require validation. It is simple, if you think that validating more processes and products will help you avoid problems in the future, you are wrong. The reasons are common sense. Validation…

… costs time and money more during implementation

… increases operational cost to maintain

… reduces your flexibility as your science evolves

… reduces throughput/productivity of any product or process

I’ll leave it there because this really does not impact the vendor relationship…it is just a common mistake I see time and time again. Validate where mandated and nothing more.

Ongoing Support

Customer success starts with “customer”

If customers monopolize all technical support and customer success resources from the vendors with trivial requests, then the vendor teams will not have the time or the incentive to solve the hard problems which require deep expertise. As outlined in my previous article on talent management, drug development companies need to have their own balanced portfolio of talent which include internal support roles.

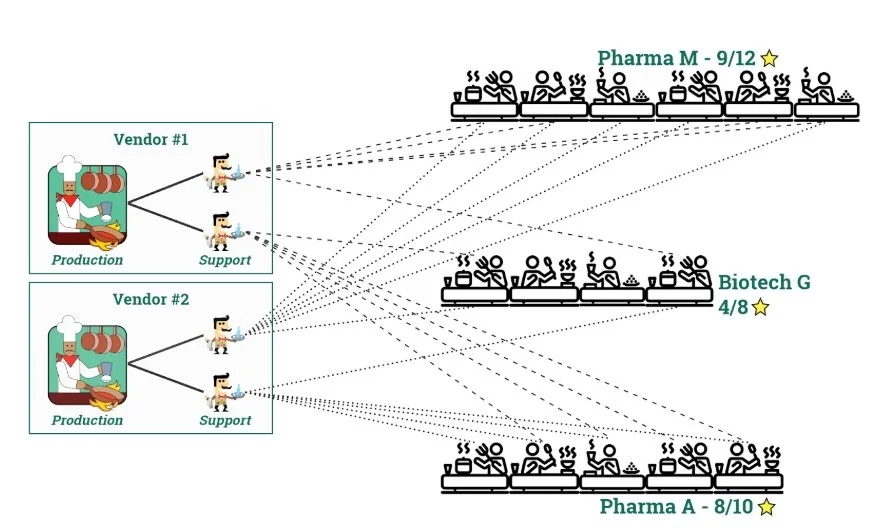

I like to use a simple restaurant analogy: The product maker is the chef, the service and support teams are the servers, and the users within biotech and pharma are the diners.

The most common resource model in industry today has all of the service and support residing within the vendor organization. Many of these support requests are trivial in nature, leading to some unhappy customers due to lack of support availability to all customers.

Using the restaurant analogy, your servers do not have table assignments and are going back to the kitchen to refill every glass of water and return every dirty dish at the expense of serving food when it is still hot.

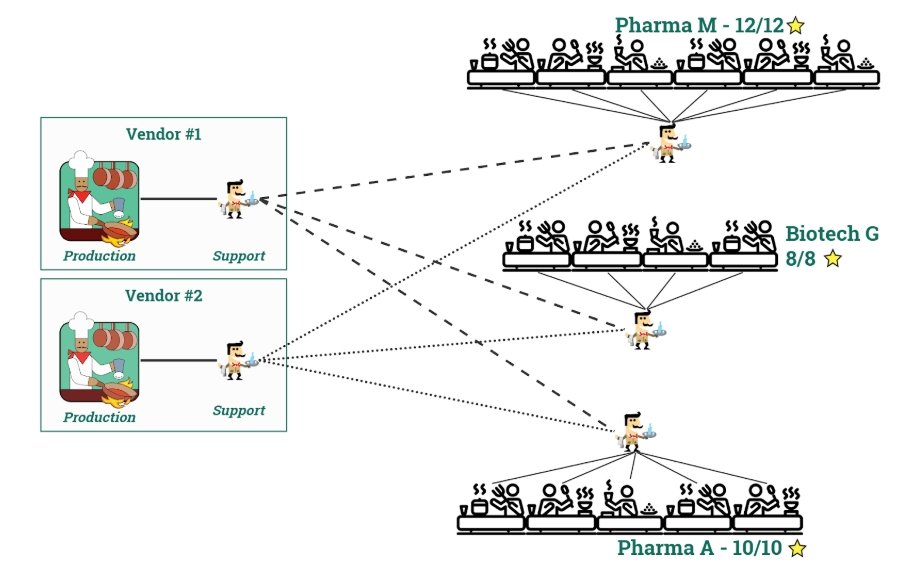

Using a model where all of the trivial support and maintenance requests are handled by dedicated internal customer roles, the vendor support burden is displaced by the in-house biopharma staff (who do not lose time in transport, etc). I have consistently seen this improve the end user satisfaction and system utilization when implemented. To round out the restaurant analogy, this is the equivalent of having a bussing station and dedicated server for the large party customers.

Bottom line - if you are not proactive in supporting your internal users, plan for mediocrity at best.

Conclusion & Thoughts on Future Improvements

I have only hit the highlights here, hopefully providing some value to both life science vendors and drug developers. The amount of time lost due to friction-filled communication and interactions adds up to loss of access to patients in need. Every tactic which adds some amount of operational efficiency maters. If some of these tactics seem beneficial but you don’t know how to get started, please feel free to reach out to me directly.

In the future, this is an area where I believe technology can help tremendously. Transparency in supply chain and AI-enabled IoT & Digital twin technology combined with data sharing between vendors and the users of their products will enable all parties to be more predictive and proactive with their product design and support resources.

I also hope that training, even at the service engineer level, for customers will become routine. This applies to both informatics and hardware products.